June 2015 WSU Dairy Newsletter

Joe HarrisonCool Temperatures and Large Particle Solids Affect Ammonia Emissions from Land Applied Dairy Manure

We have been studying the factors affecting the emission of ammonia from dairy manure for the past eight years. The major factors that affect ammonia emission at the time of application appear to be: the ambient temperature, manure treatment (anaerobic digestion of manure), large particle solids, and incorporation.

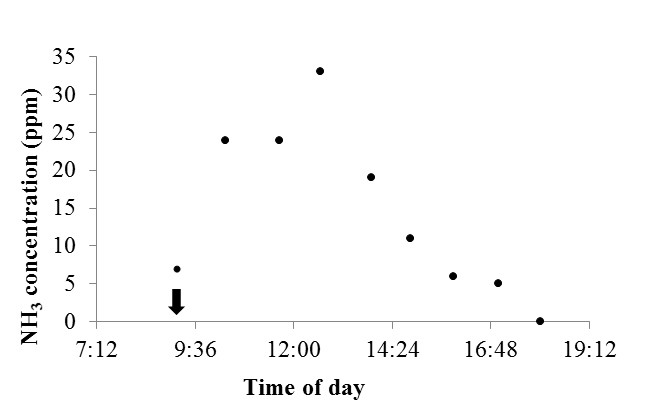

During the summers of 2010, 2011 and 2012 we conducted twenty-two manure application studies looking at the effect that various types of dairy manure had on ammonia emissions when applied to grass which was to be harvested as silage. In particular, we wanted to understand the impact that anaerobic digestion and large particle manure solids had on ammonia emissions. Figure 1 shows the typical pattern of ammonia concentration throughout the day of manure application.

Due to the cooler climate of the Pacific Northwest, it is common to apply manure at ambient temperatures below 60 degrees Fahrenheit. We found the that 60 degrees Fahrenheit was a critical temperature as we were not able to observe ammonia emissions on the day of manure application when it was cooler than 60 degrees.

We know from studies with anaerobic digestion (AD) of dairy manure that the amount of ammoniacal nitrogen can be greater in AD manure. This is due to the conversion of organic-nitrogen to ammonia-nitrogen by microbes in the anaerobic digester. This observation led us to assume that AD manure would lose more ammonia when land applied, when compared to non-AD (or raw manure). What we found in 2010 was that since AD manure had the large particle solids removed prior to storage, the AD manure actually had less ammonia emitted after land application than non-AD manure with large particle solids (see Figure 2). The reduced NH3 losses from liquid manure without large particle solids was due to the promotion of manure infiltration into the soil, consequently reducing the manure exposure time on the ground surface.

In 2011, we added an additional manure type, non-AD with large particle solids removed. When this manure type was compared to AD manure, and non-AD manure with solids, it was clear the effect that manure solids have on increasing ammonia emissions. Our data suggest that the ammonia emission were reduced by ~40% (see figure 2) when large particle solids had been removed.

Complete data published in Sun, F., J. H. Harrison, P. Ndegwa, and K. Johnson. 2014. Effect of manure treatment on ammonia and greenhouse gas emissions following surface application. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. DOI 10.1007/s11270-014-1923-z

Joe Harrison, Livestock Nutrient Management Specialist, WSU Puyallup, jhharrison@wsu.eduAmber’s Top Ten Tips: Understanding Heat Stress

Heat stress is bad news for dairy cows. We often hear about abnormal heat waves that roll through regions leaving behind millions of dollars of damage, but what about the losses incurred during a typical summer? Across the U.S., the economic losses attributed to heat stress are approximately $100 per cow per year. With summer knocking at our door, have you considered how hot weather impacts the cows on your dairy?

Interesting facts about heat stress in dairy cows:

-

Temperature-humidity Index (THI)

THI is commonly used to gauge the severity of heat stress dairy cows experience under specific environmental conditions (ambient temperature and relative humidity). THI ≥ 72 is categorized as heat stress; however, recent research has indicated that the heat stress threshold should be lowered to a THI of 68.

THI = ambient temperature – [0.55 – (0.55 * relative humidity/100)] * (ambient temperature – 58.8)

Ambient temperature is recorded in Fahrenheit and relative humidity is recorded as a percentage.

-

Core Body Temperature

As THI increases and, subsequently, core body temperatures increase, cows spend more time standing rather than lying down. Cows with rectal body temperatures ≥ 102.2°F (measured in the afternoon) are at risk for decreases in milk production and fertility.

-

Water Intake

Cows will consume 35 – 50% more water during heat stress conditions. Ensure cows have access to an adequate supply of clean, fresh water.

-

Feed Intake

Heat stress causes decreases in feed intake during the daytime, decreases in feed efficiency, and decreases in nutrient absorption. Nighttime “slug feeding” may lead to higher incidences of acidosis.

-

Milk Composition

Cow exposure to environmental heat stress has been linked to higher milk somatic cell counts and bacterial counts, with lower milk fat and protein percentages.

-

Cooling Strategies

Natural ventilation, fans, sprinklers/misters, shade access (esp. open lot dairies), and cooling pads all offer heat stress abatement for dairy cows; however, each dairy needs to assess which strategy will work best for each facility. Adjustments to feeding schedules, ration formulations, and stocking densities may also assist with heat stress abatement.

-

Milk Production

Depending on the severity of heat stress conditions, cows will decrease their milk production by 10 – 50%.

-

Reproduction

Conception rates during heat stress can plummet by almost 20%. For example, a dairy with a typical conception rate of 31% fell to a conception rate of only 12% during hot weather.

-

Health

Higher incidences of mastitis, respiratory problems, retained placentas, and higher respiration rates have been diagnosed in cows under heat stress conditions.

-

Gestation

Calves exposed to heat stress during the last 45 days of gestation have lower birth weights, lower weaning weights, and depressed immune systems.

V.S. is No B.S.!

On May 29, Dr. Keith Roehr presented a webinar about the 2014 Vesicular Stomatitis (VS) outbreak in Colorado. Dr. Roehr is the Colorado State Veterinarian. He reported that between July 4, 2014 and Jan. 29, 2015, his office made 556 investigations and ultimately quarantined 370 premises that tested positive for VS. The late onset of Colorado’s winter in 2014-15 was blamed for such an extended outbreak duration.

What is VS?

VS is a contagious viral disease of all hoofed animals—particularly equines, swine and cattle; sheep, goats and camelids are affected less often. The virus occasionally spreads to humans and causes a flu-like disease and blisters in rare instances. It is believed to enter a herd via insect vectors (black flies, midges, sand flies, etc.) and then spread primarily through additional insect activity within the herd. Little transmission is believed due to direct livestock contact, animal movement, and mechanical means, such as contaminated equipment and facilities.

Signs of Illness

Why is VS Important?

VS is present in the U.S. and occasional disease outbreaks occur. Also, although VS is very contagious and can cause many cases of illness on premises, animals rarely die from it. Nevertheless, the disease is particularly important for several reasons:

- The signs of VS are similar to three foreign animal diseases not present in the U.S.: foot and mouth disease, swine vesicular disease, and vesicular exanthema of swine. It is essential to differentiate VS from these other diseases quickly so the entry of one of these exotic diseases can be identified and dealt with promptly.

- VS is infectious—outbreaks in the U.S. restrict some international trade until the outbreak is contained.

- Its similarity to important foreign animal diseases make VS a reportable disease in the U.S.

- Animals afflicted with VS are in pain, stop eating, lose weight and produce less milk. A widespread outbreak could cause significant animal suffering and economic losses. Dr. Roehr shared that economic losses of dairy farms involved in the Colorado outbreak were over $1M on some farms when decreased production, increased labor, reduced livestock marketing options, diagnosis and treatment costs were considered.

Control Measures

A vaccine for VS is not available in the U.S., so control of biting insects is the major component of VS control and prevention:

- Reduce exposure to flies by reducing pasture time.

- Eliminate stagnant water or keep livestock away from wet areas where insects of concern are more common.

- Use effective approved insect repellents.

To reduce mechanical transmission of the virus, equipment and tools should not be shared between farms. During outbreaks, healthy animals should be monitored closely for early signs of illness (fevers and vesicles) so they can be isolated from other animals quickly.

State and/or federal veterinarians are responsible for making the diagnostic determination in cases of VS. They issue quarantine orders, stopping animal movement to and from affected premises. They also advise owners about disinfection measures and isolation of affected animals to protect unaffected animals on the premise.

Conclusions

VS outbreaks are a reminder for livestock owners to develop, fine tune, or brush the dust off farm biosecurity plans. Livestock owners will be the first line of defense in the event of the entry of a foreign animal disease into the U.S. Early detection is our best hope for containing economically-important diseases such and foot and mouth disease. Monitor your animals regularly for signs of illness and call your veterinarian immediately if you see vesicles, blisters, erosions, or the other signs previously mentioned. Let’s hope it is “only” VS or something more innocuous.

A recording of Dr. Roehr’s webinar is available from Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. He discusses dairy cattle involvement in depth.

For Additional Information

- Vesicular Stomatitis (Iowa State University Center for Food Security and Public Health)

- Vesicular Stomatitis Factsheet (USDA APHIS) (pdf)

LIVESTOCK OWNERS: If you ever notice a vesicle, blister, ulcer or erosion on an animal’s mouth, teats, prepuce or feet, contact a veterinarian at once. Odds are this is not a foreign animal disease, but if it is, every hour of diagnostic and containment delay means an exponential increase in the cost of the outbreak, in both economic impact and animal suffering.

Dr. Susan Kerr, WSU NW Regional Livestock and Dairy Extension Specialist, kerrs@wsu.edu